In 1974, when Dr Challoner’s Grammar School celebrated its 350th anniversary, I was a 14-year-old pupil there. I bought this book in the hope of being able to relate to much of the stories related in its chapters. I was far from disappointed. It is helpfully divided into three parts, the third part being titled “The Modern School, 1962-2024.” This helps readers to focus on that part of the school’s history to which they can best relate.[1]

The author, Dr Mark Fenton, is a historian by training and was the school’s headmaster from 2001 to 2016. He is thus in an excellent position to write this book. He meets expectations in every respect.

Grammar schools have always been very reputation-conscious and seen themselves as state private schools. Dr Challoner’s is no exception, as is evident from the title of Part 3, Chapter 11 (“The Best Education Money Can’t Buy”). With this in mind, it must have been tempting to gloss over certain events of the 1970s and 1980s, which is generally portrayed as the lowest point in the school’s history. The title of Chapter 9 (“Under Siege”), which covers most of this era, may come across as somewhat emotive, but as a pupil there at the time, I can vouch for the fact that it reflects the spirit of the age.[2] The school was in fear of being turned into a comprehensive, something seen as the very embodiment of evil in those days. That fear led to the eye being taken off the ball, with the result that a “Jimmy Saville” teacher sexually abused pupils of the school and escaped justice for two decades. The temptation to omit this sorry tale must have been great; Dr Fenton deserves the highest praise for telling it like it was, and for stating that the whole affair “took a terrible toll on the boys involved.” That is a very diplomatic understatement; as this review is written, historic abuse at Dr Challoner’s is being investigated by a top law firm.[3] The desperation of many parents of the time to see this affair swept under the carpet has proved, and still is proving, counter-productive; the desire for a 90-year-old parent to see sex abuse covered up can be as damaging to a 60-year-old child as a similar desire on the part of a 40-year-old parent can be to a teenage child.

Two other educational hot topics that affected the school in past decades are developed skilfully in the book, namely accountability versus autonomy and single-sex versus co-education. In the past, private and grammar schools guarded their freedom jealously and did not consider accountability and outside scrutiny to be necessary. Their reputation spoke for itself after all, They were supported 100% by parents, who had a faith in such schools that can best be described as Titanic. In Part 3, Chapter 10, Dr. Fenton pulls no punches in relating the reluctance with which Dr Challoner’s accepted the climate of accountability that, thank God, was becoming the norm by the early 2000s. It hastened the retirement of John Loarridge, the headmaster for most of my time at the school; he is reported in the book as viewing the national curriculum as “a vast waste of time.” But in reality, the case for greater accountability is made by revelations that emerged in the post-Loarridge era. On taking office in 1993, Mr. Loarridge’s successor, Graham Hill, identified, as one of his first priorities, improving discipline. No grammar or private school willingly admits to deficiencies in discipline, so it is to Mr. Hill’s credit that he acknowledged, implicitly at least, that it needed to be improved. As a pupil in the 1970s I saw it break down completely, and the book mentions a case of a boy expelled for selling cannabis – in 1970! But when I aired my concerns, as a 17-year-old sixth-former in 1977, I was told very sternly to “keep it to yourself, otherwise it will reflect badly on you.” Mr. Hill reasoned, correctly, that this softly-softly, Silent Generation approach was no longer tenable in the coming era of less autonomy and greater accountability. His success in dragging the school into the 21st century is well documented in the book.

With regard to the single-sex versus co-ed debate, a long-standing preconception of mine, namely that it had been the school management of the time who had desperately wanted Dr Challoner’s to be segregated sexually, is debunked. Mr. Porter, the head at the time of the changeover in 1961, considered the separation of the boys from the girls to be “a very sad day.” What the book glosses over somewhat is that single-sex education came into vogue at Dr. Challoner’s in the 1970s, largely due to the changing demographic of the parents, most of whom were of urban-working-class-made good backgrounds, the epitomes of the MacMillan never-had-it-so-good era. Having themselves been educated generally in single-sex grammar school environments, they preferred it for their sons. Mr. Loarridge was on their side ; I well remember travelling to St Paul’s Cathedral for the 350th anniversary celebrations on a special Metropolitan line train commissioned for this purpose and not being allowed to mix with the girls who also attended. Fortunately, in 2016, the school came almost full circle and admitted girls into the sixth form of the boys’ school.

One incident related by Dr Fenton that is of special significance to me is the case of the bulldozer damaged, allegedly by residents of Longfield Drive, a neighbouring street, in protest against a new school entrance that was then under construction. What is not clear from the book is the reasons behind such behaviour, other than basic nimbyism. But whatever the reasons, that entrance was badly needed on road safety grounds. Previously, school coaches had parked outside the school obstructing the sightlines of boys crossing the main Chesham Road on which the school is situated, creating a lethal road safety hazard. I was probably nearly killed more times than I realise when crossing that road. Fortunately, child safety trumped nimbyism, thus enabling the new entrance to go ahead and school coaches to park in the school grounds.

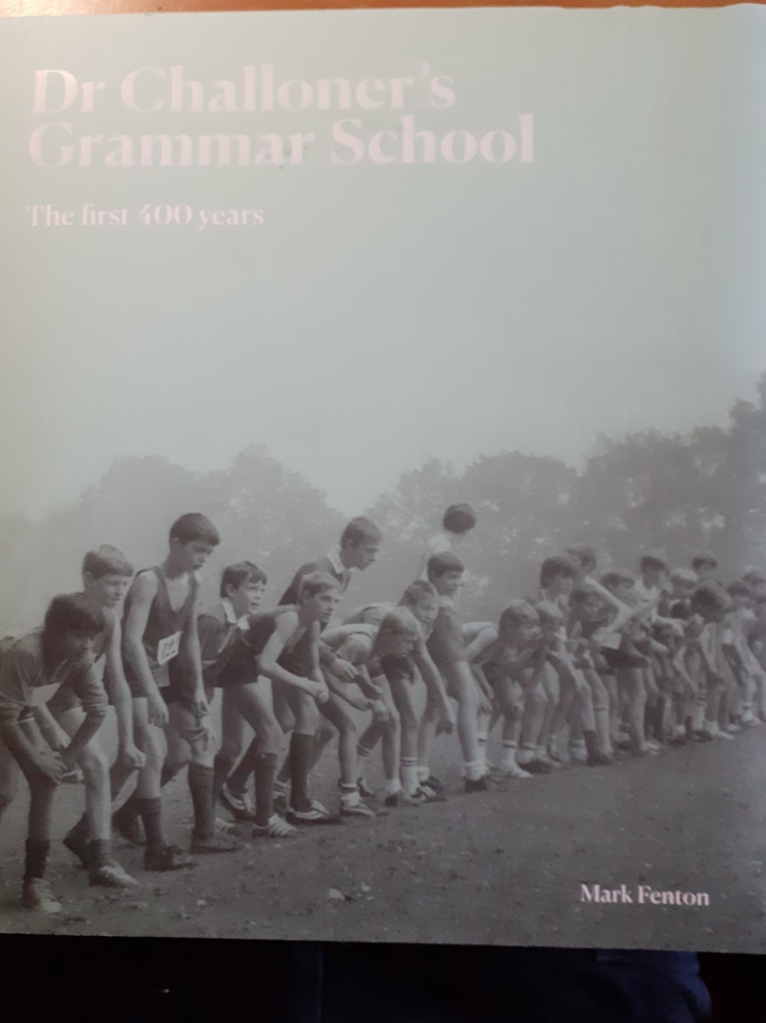

The book is generously illustrated with photos of each era. In Part 3 is a photo of the under-13 football team in 1971. I don’t recognise any of the pupils in the photo, although this was my first year at the school, but I do recognise Mr. Green, my first-year geography teacher, who was the team’s captain. Mr. Green did not think much of my ability as a geographer; I still have a 1974 end-of-year report on which he comments that “geography is not one of David’s better subjects.”

On reading this book, one can be confident that, in its 400th anniversary year, Dr. Challoner’s has genuinely moved with the times. This was clearly not the case on its 350th anniversary. My thoughts at the time, as a mere 14-year-old, remember, were that it was stuck in the past and resolutely determined to move any which way but forwards. Half a century on, I feel vindicated. I had expected that era to be given short measure in the book, but this is not the case. Consequently, for the balanced and comprehensive presentation of the school’s history, I give the book a five-star rating. It was well worth a 40-mile round trip to Amersham to purchase it at a cost of £30, money well spent. I commend it to the House.

[1] The book is available to purchase from Waterstones of Amersham or directly from the school. See Anniversary Book – Dr Challoner’s Grammar School (challoners.com). It is available in hard copy only.

[2] My own book about that troubled era, CALLING IN THE CAVALRY, is available, in e-book format only, from Amazon. See CALLING IN THE CAVALRY: EDUCATIONAL SNOBBERY, BULLYING AND SEX ABUSE AT ONE OF BRITAIN’S TOP PERFORMING STATE SCHOOLS eBook : LAWES, DAVID: Amazon.co.uk: Books

[3] Alleged abuse by former teacher Neil Bibby at Dr Challoner’s Grammar School investigated by lawyer | Leigh Day